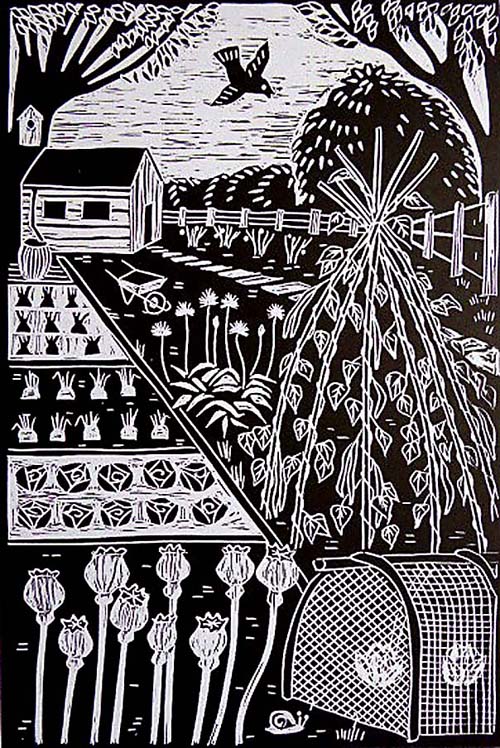

My name is Jane Dignum and I am a printmaker living in York, North Yorkshire. Although I like to try out lots of printmaking techniques, I tend to focus on Linocut and I also make collages from pieces of my prints. The city of York and the county of Yorkshire are great sources of inspiration for my work as is my allotment and the wildlife that I see there.

How and where did you learn to print? How long have you been printmaking?

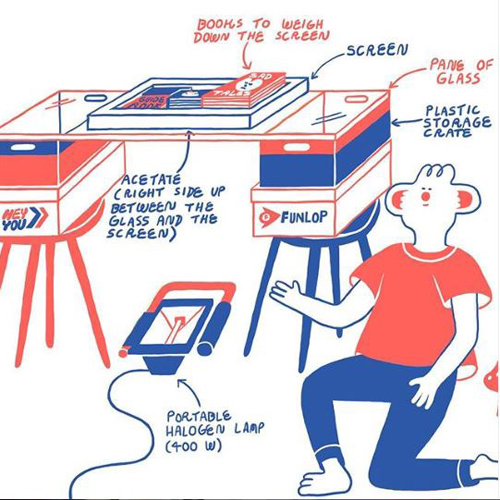

I have been printmaking on and off for at least twenty years. I used to mainly draw and paint but I have a tendency to become obsessed with fine detail. Printmaking allows for more stylistic freedom and to a degree, you are out of control of some of the process which is very exciting. I taught myself to relief-print as all I needed was a material such as Lino, a few tools, paper and ink. It is a very accessible form of printing and I was able to achieve satisfactory results just by working at the kitchen table. Then I completed a degree in Fine Art at Leeds College of Art. I was working full-time as a teacher and so the part-time course took six years to complete as tutorials were held in the evening and other study units were fitted into school holidays. It was aimed at people who were working and you had to be pretty dedicated to finish it. It was here that I was introduced to printmaking using all of the facilities that a print studio had to offer and I was hooked. Following this, when I left college, I did not have access to the same resources and so I stopped printmaking for a while. Then, I attended a Linocut workshop in York where I was introduced to the Hawthorn etching presses which are made locally. I took the plunge, invested in a press and this was the real start of my printmaking journey.

Describe your printmaking process.

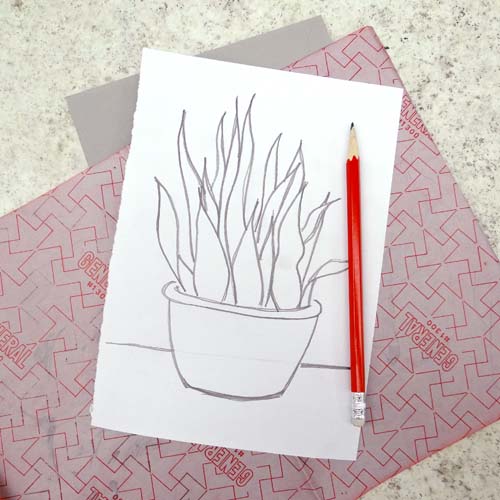

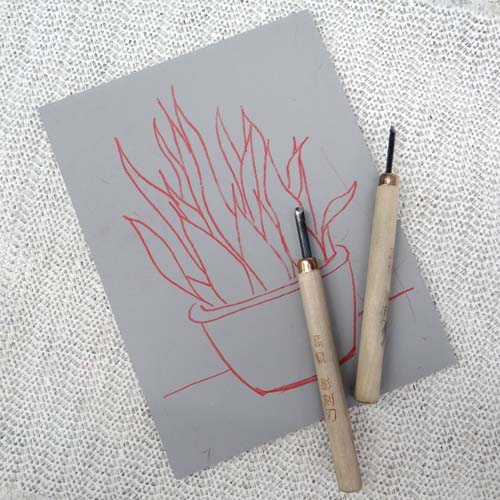

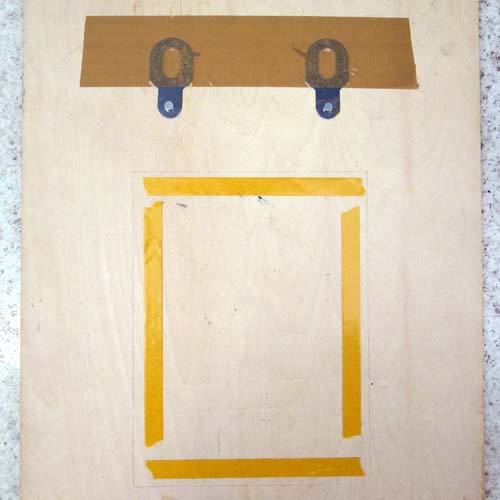

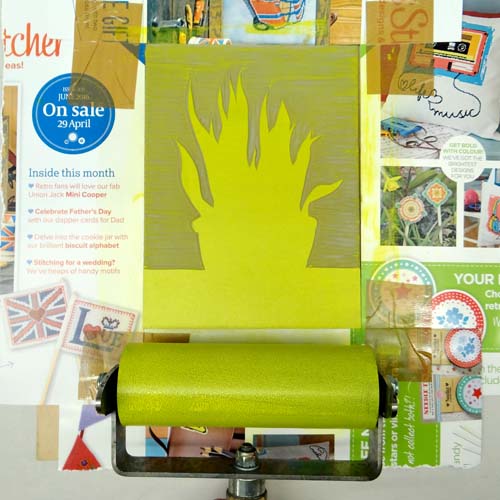

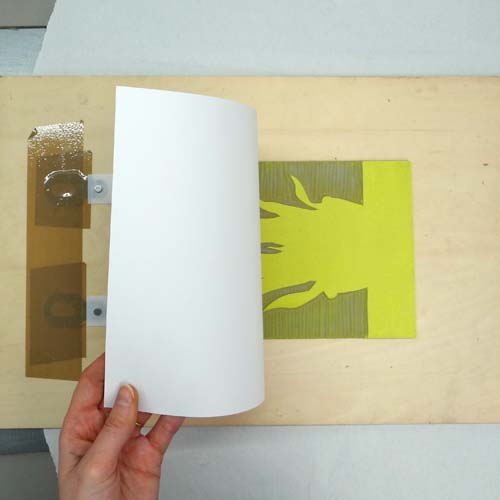

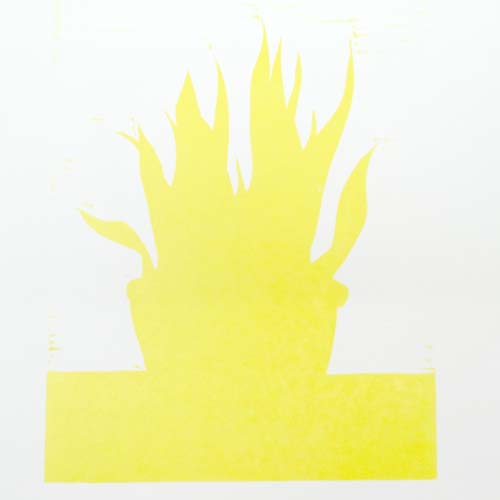

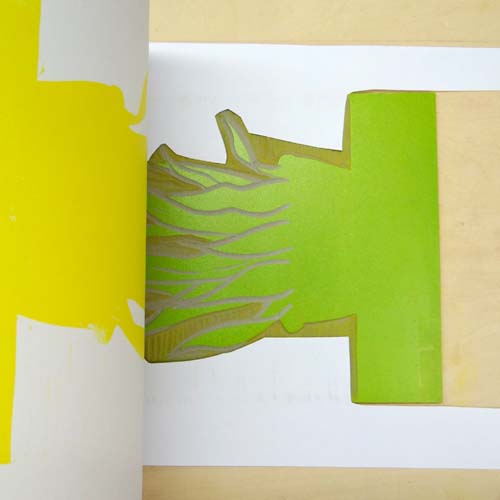

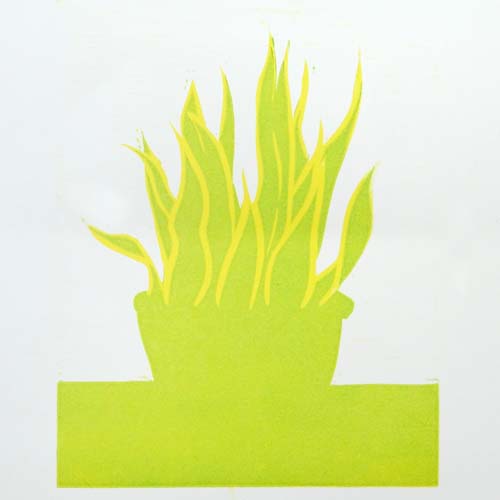

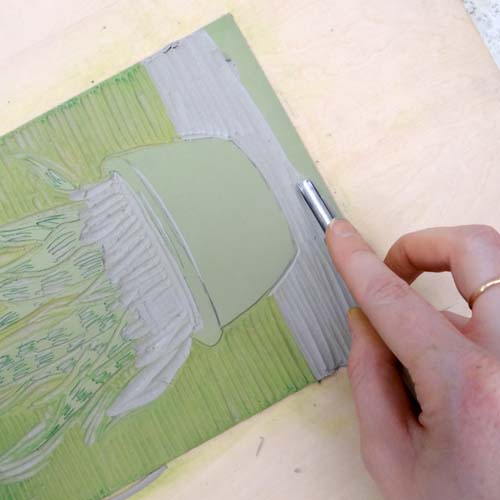

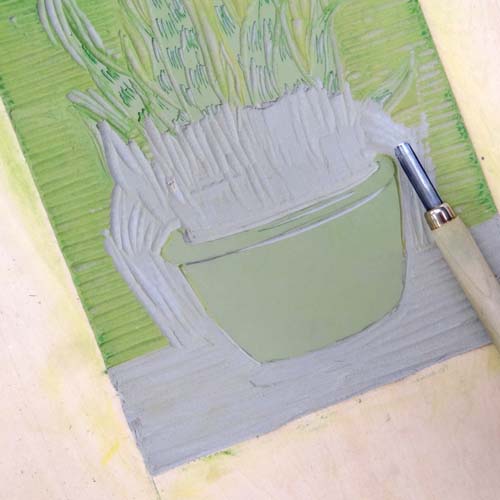

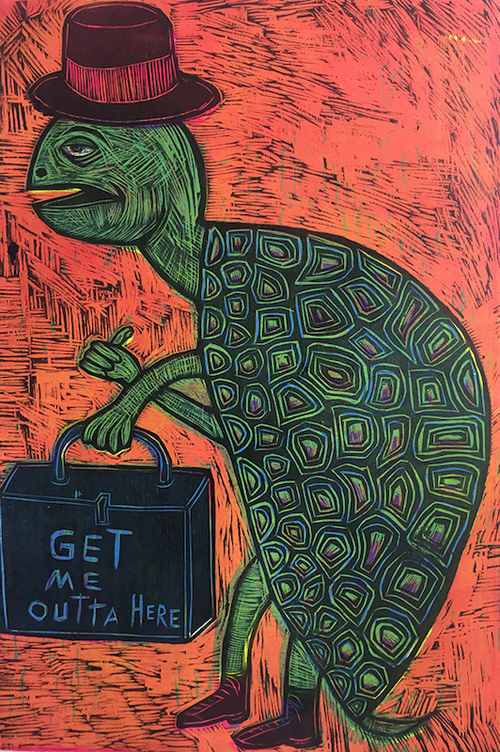

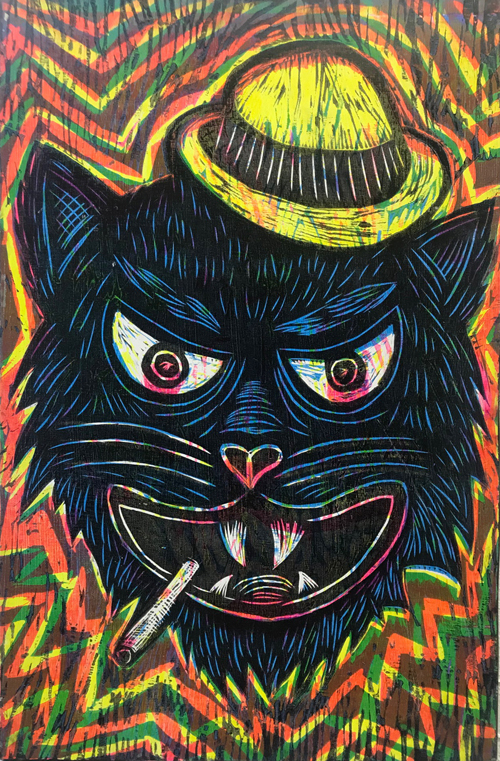

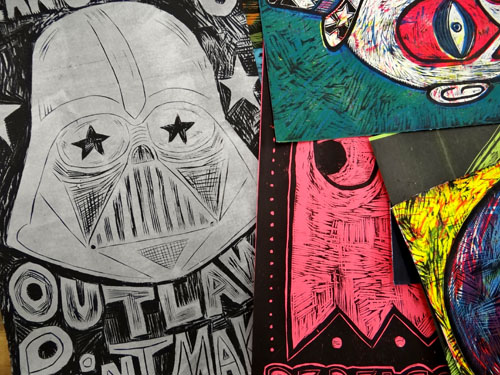

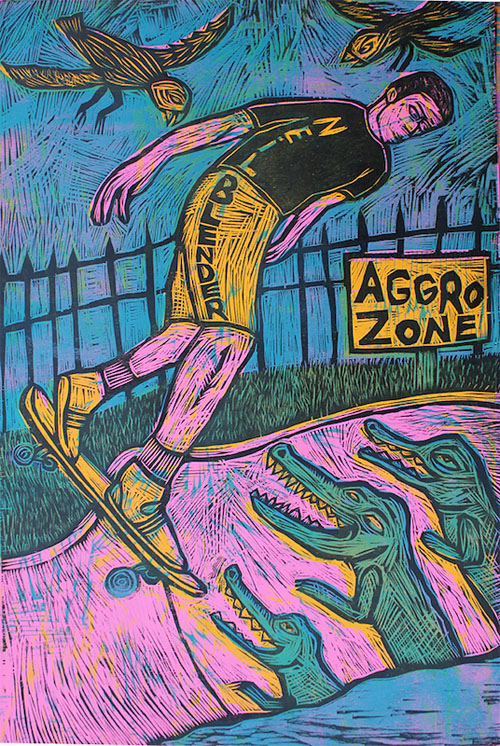

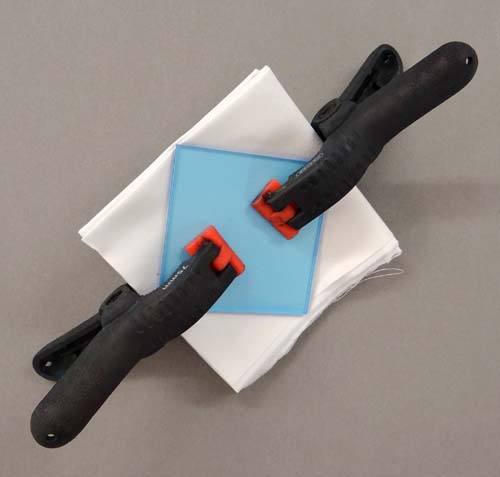

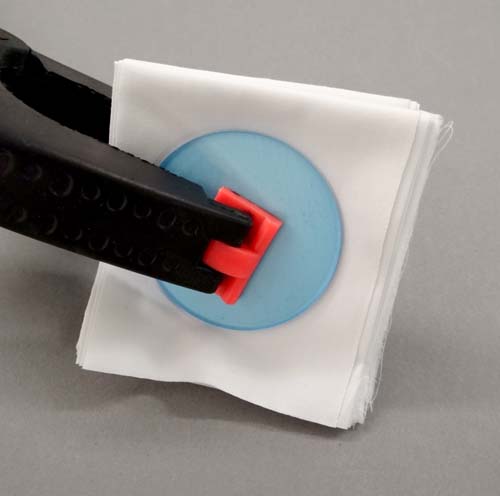

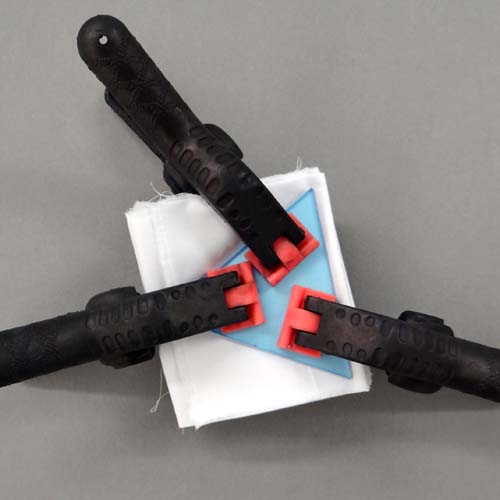

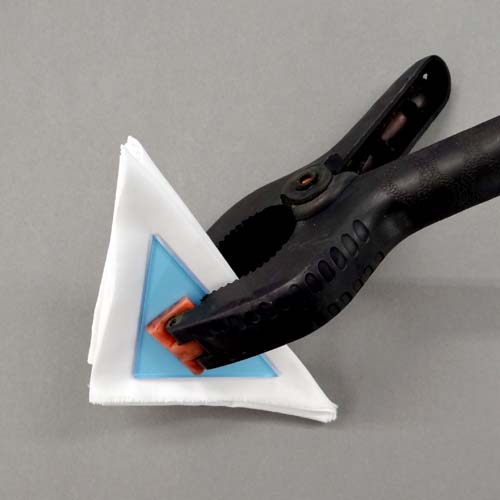

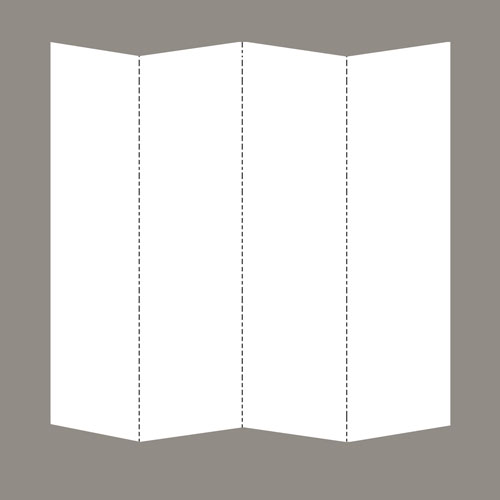

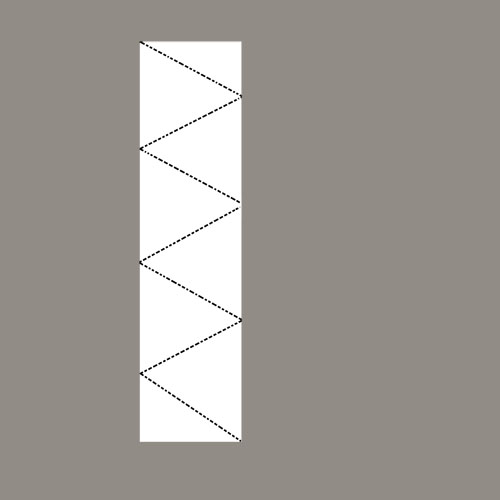

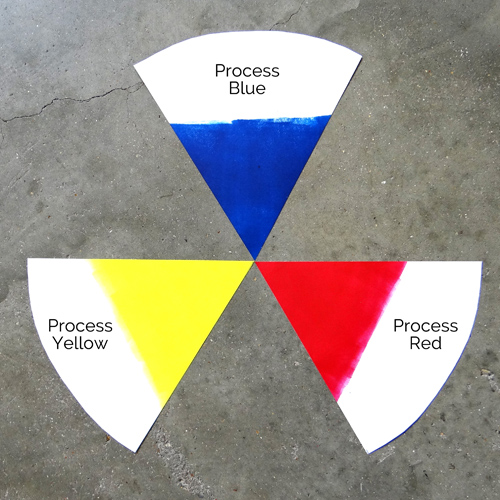

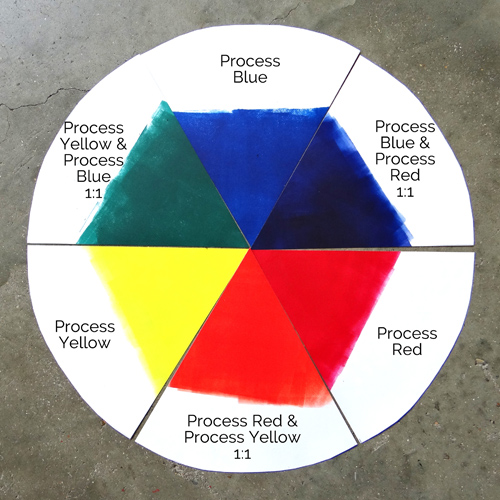

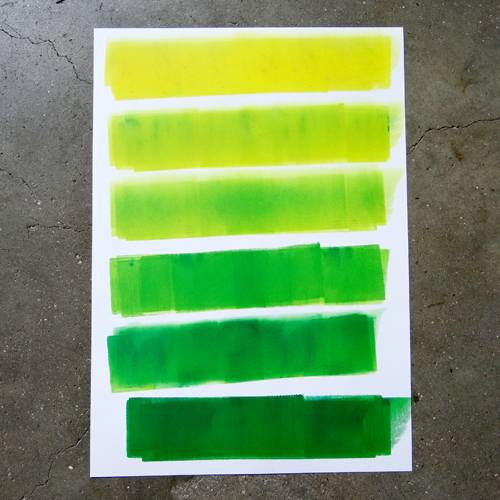

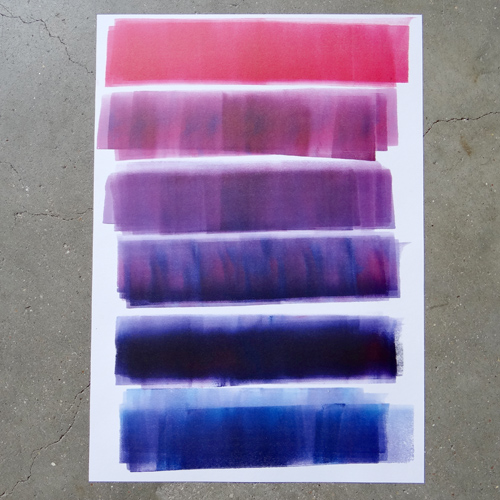

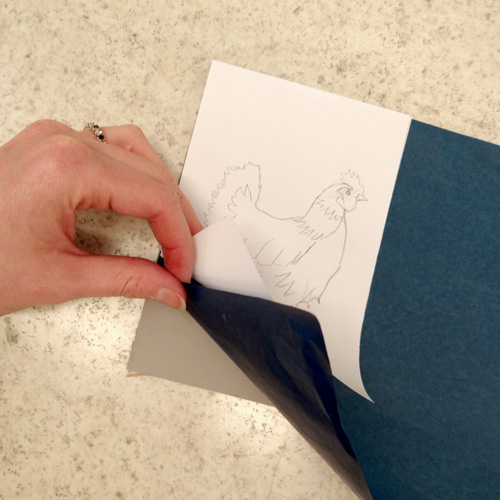

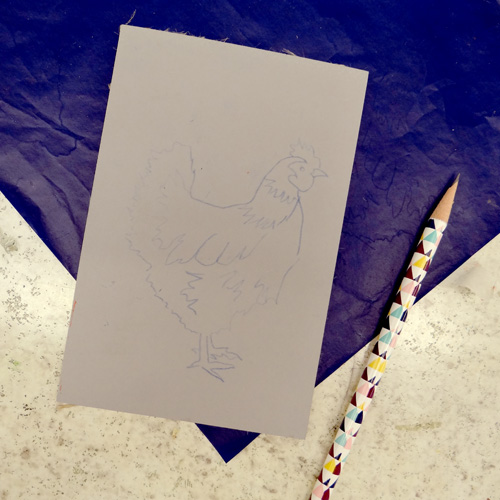

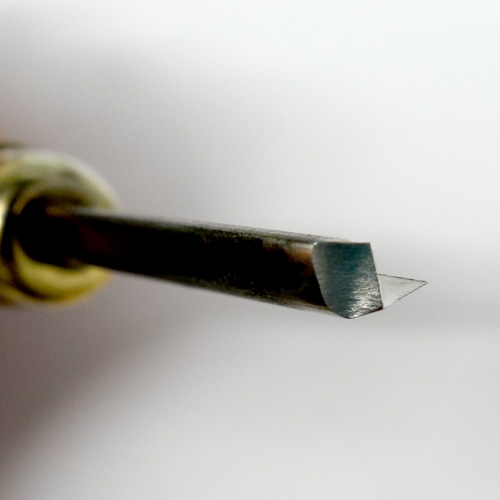

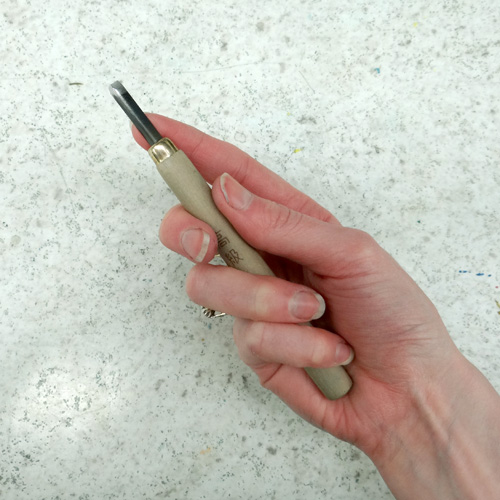

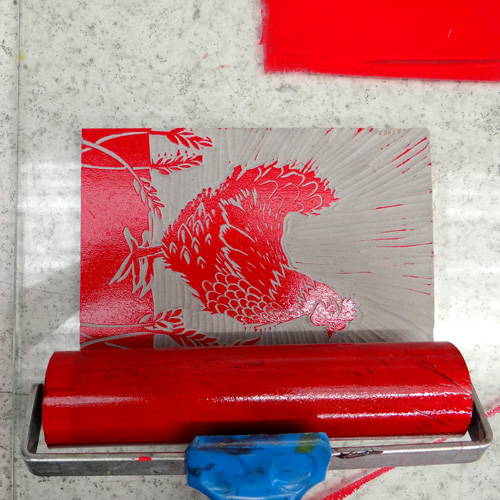

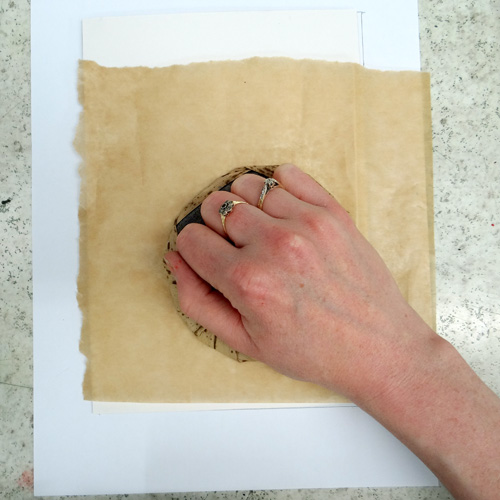

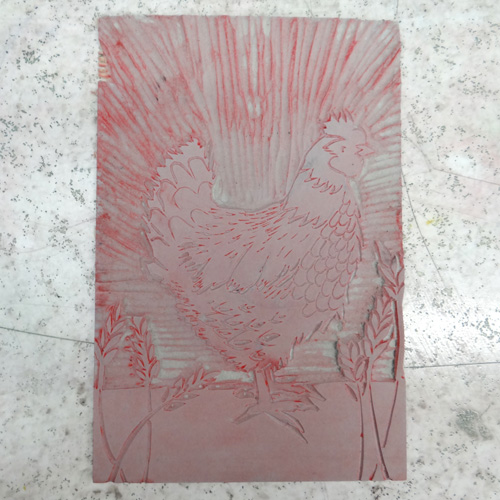

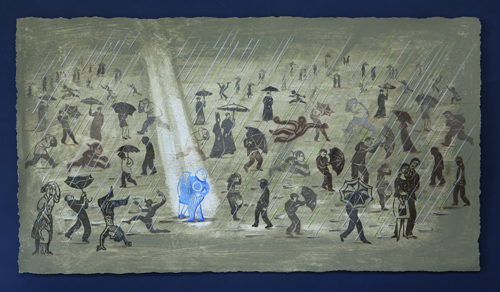

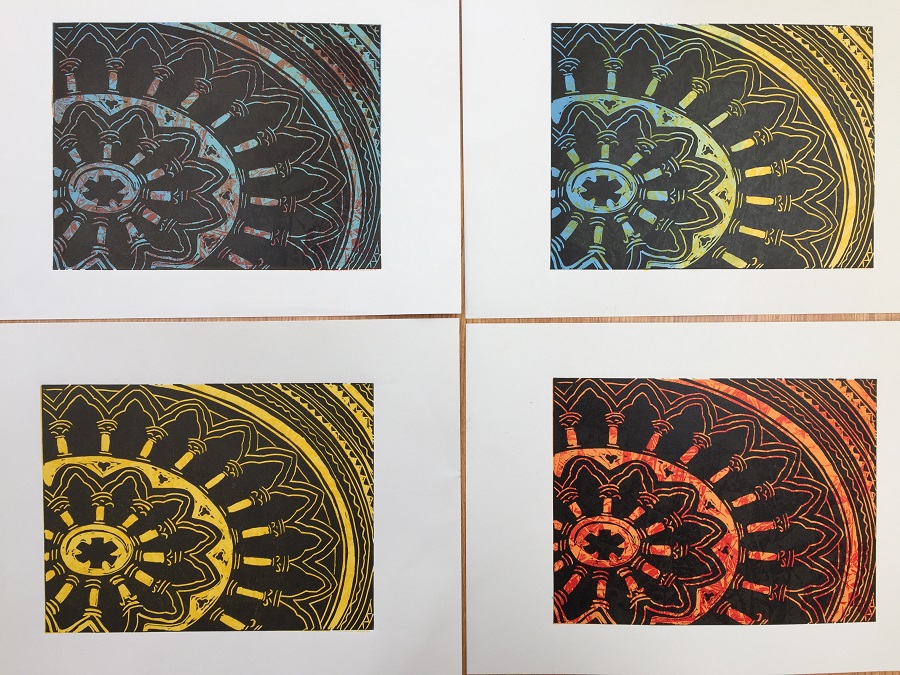

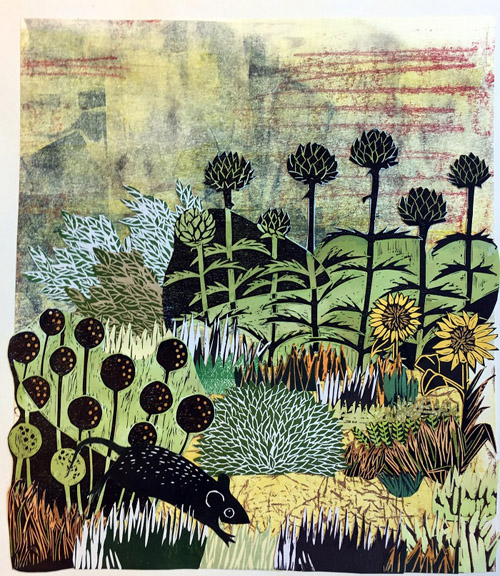

I have various ways of working and I often combine different methods. I always carry a small sketchbook and a camera with me wherever I go and am constantly on the lookout for interesting images and ideas. I then work out a design on paper or using an iPad. The iPad is useful for loading up my photographs and layering them to create a new composition. I then trace the design onto vinyl which I then carve. Sometimes I feel that a design works best just in simple black and white but at other times I feel that some colour is needed and I have various ways of achieving this. The ink that I use is oil-based so it allows me to hand-colour after the ink has dried using a water-based medium. I enjoy this as it combines my love of printing as well as painting. Another method I use is to transfer my design by printing it using Perspex onto another piece of vinyl. I then create separate printing plates for each colour, using the trusted Ternes Burton pins and tabs to register each one.

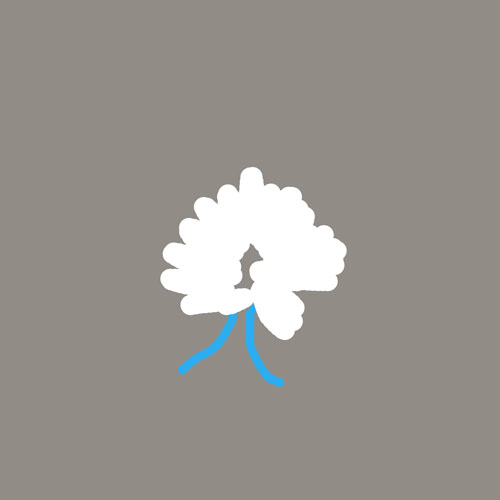

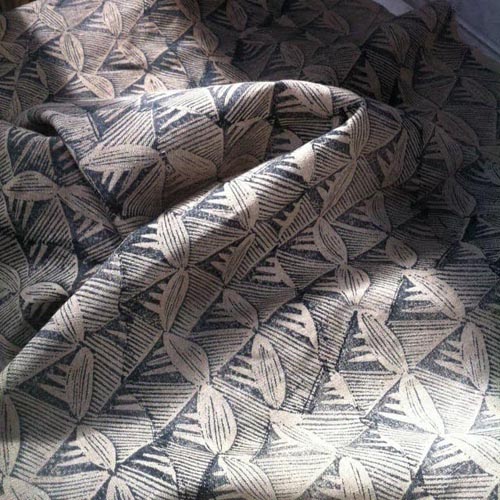

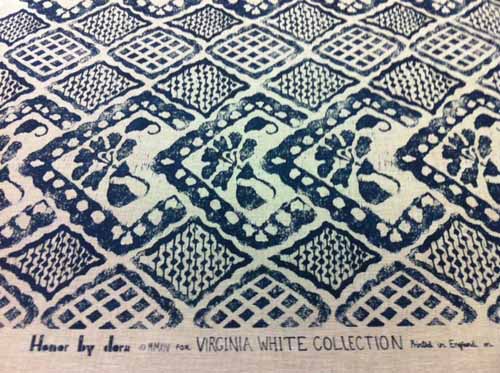

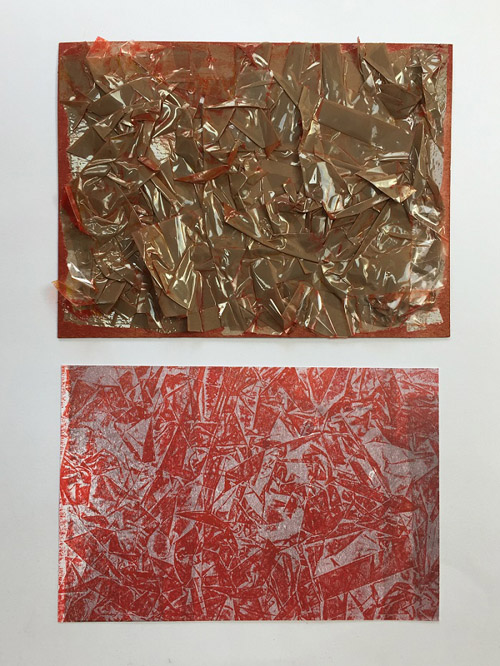

Although I don’t strictly create collagraph prints, I like to use collagraph techniques to create textures and interesting backgrounds. I stick all manner of materials onto card and try printing from them. Matchsticks, bubble wrap, cellotape, sandpaper all work very well. I am always on the lookout for different materials and keep examples of the results in my sketchbook. Sometimes, I chop up these experimental pieces to rearrange to make collages. I also use prints where maybe one corner hasn’t printed well but the rest is fine. I reuse the good bits and combine them all to create a unique piece. Nothing is wasted!

Where do you work?

I work in my studio which has been purpose-built at the back of my house. It is there that I create my prints on my wonderful etching press. I usually spend my days carving, printing, collaging and experimenting with new ideas. I work in isolation which is why I have joined a local group of printmakers. We meet each month and discuss ideas, techniques and share tips. I believe that this is very important, so that your work does not become stale. We are a very active group, organising talks about printmaking, print fairs and exhibitions.

What inspires you?

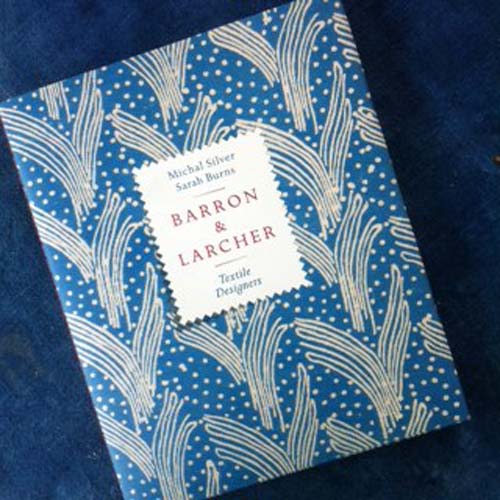

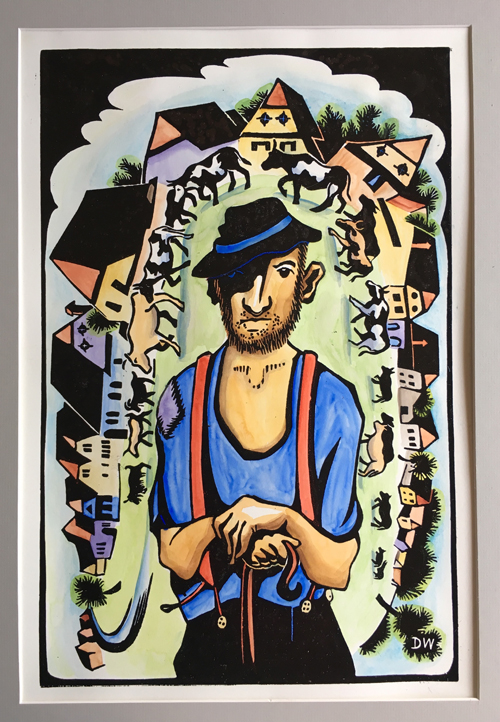

I love to visit art exhibitions of all kinds and I have been influenced by too many artists to list them all. I have always loved David Hockney’s work and am fascinated by his etchings of The Fairy Tales of the Brothers Grimm. I also admire the Linocuts of Edward Bawden especially those showing architectural structures such as Borough Market and Covent Garden. I must also mention Robert Taverner, who is probably the greatest influence of all on me. His atmospheric countryside scenes with the sweeping grasses and stylised trees are just fantastic.

What is your favourite printmaking product?

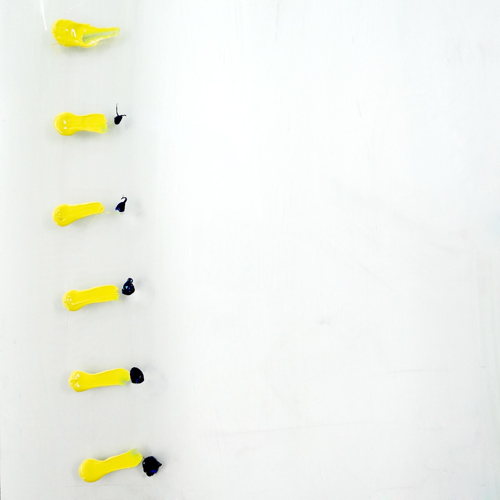

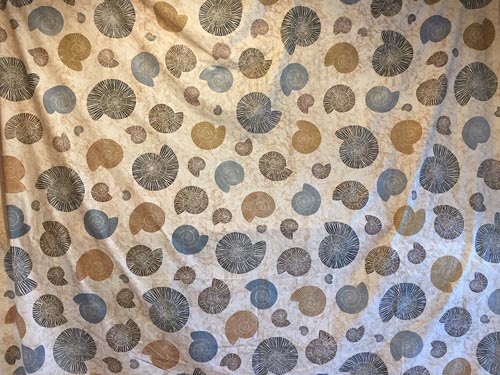

My favourite printmaking product is probably the range of Hawthorn Stay Open Inks. I use them all the time. I print with them onto all types of paper as well as on occasion, fabric. I can’t vouch for how well they would wash however! I have a printed onto a large white piece of fabric which I occasionally use as a screening off curtain at shows. I used scrunched up parcel tape stuck onto a large piece of card which I inked up and then printed over the entire piece of fabric. Once this was dry, I then printed ammonites in a range of sizes and colours all over the top of the background print. I had to print each ammonite separately. Lots of people admire this when they see it and I am probably the most proud of this work. It took about two weeks to create and dry.

I often feature ammonites in my work as I see them set into the rocks along the coast at Whitby where I like to walk and fossil hunt. In 2015, I submitted some images to become part of the York Open Studios annual art event. It was a requirement to submit digital images as well as one actual physical piece. I submitted a print which featured ammonites and was successful at being selected. I have exhibited at York Open Studios three more times since then. I feel that the ammonite has been a lucky image for me and I use it as a logo on business cards and my online shop.

Where can we see your work? Where do you sell?

I sell my prints on Etsy and my designs are transferred onto a range of items by Redbubble. Both of these are available online. I also supply my prints to local galleries such as the Blossom Street Gallery in York and the Craft Centre and Design Gallery which is situated in the centre of Leeds. I also sell at art and print fairs in the Yorkshire area and I always use social media to show my latest work as well as to announce my up and coming events. Many of my designs are published as greetings cards and other items of stationery by Green Pebble, a greetings card company who sell throughout the UK as well as abroad. In the near future, I intend to run Linocut workshops in my studio for small groups of up to four. I will post the dates on social media platforms as well as on my website.

What will we be seeing from you next?

I am about to start working on some prints which incorporate stencils. This was inspired by some bold monoprints that I recently saw at the Venice Biennale by an artist called Ulrike Müller.

Do you have any advice for other printmakers and creatives?

My advice to other creatives would be to always be looking out for new ideas, never be afraid to try new things and just keep on creating.

Find me at:

Website: www.janedignum.com

Etsy shop: JaneDignumArtworks

Redbubble.com : Jane Dignum

Instagram: janedignum

Twitter: @janedignum

Facebook: Jane Dignum Artworks