Scroll through the list below to find definitions and explanations of common printmaking terms:

Acid-free – refers to papers that are made with an alkaline pulp, usually with calcium carbonate added. Acids contribute to the deterioration of paper and therefore of prints.

Aisuki – a rounded, bevelled chisel tool used in Japanese Woodblock Printing, often used for clearing areas of wood. You can find Aisukis here.

A la poupée – an intaglio printmaking technique in which different coloured inks are applied to a plate with a wad of fabric.

Aquatint – an etching technique in which tones are achieved. Usually, a metal plate is given an acid-resistant coating before being placed in an acid bath. The acid bites into the plate, producing a surface that can hold ink for printing. Tonal variations are achieved by varying the length of time in the acid bath.

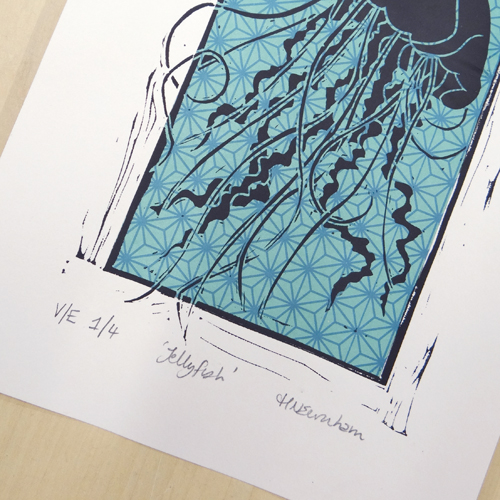

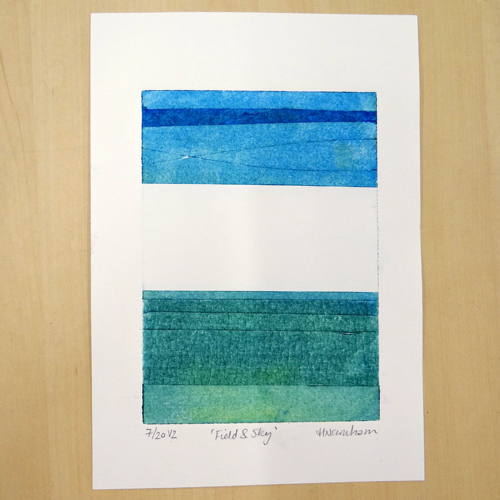

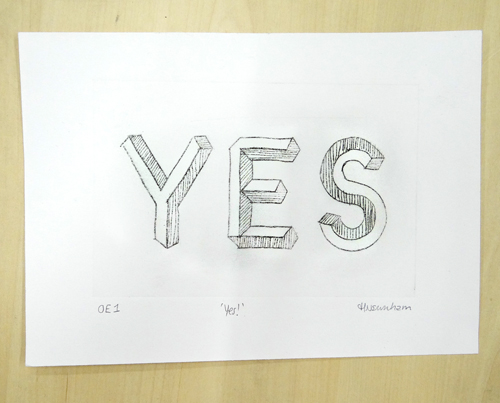

Artist’s Proof (AP) – Artist’s proof prints are made by the artist to check the print quality and design before printing an edition. Artist’s Proof prints usually shouldn’t exceed 10% of the overall number in the edition. They are usually identical to the edition but may sometimes include slightly flawed prints omitted from the edition. See our blog post on editioning prints for more information.

Baren – a disk-shaped printmaking tool used to hand burnish a print by rubbing it over the surface of the paper when it is in contact with the inked-up block. Find barens here.

Bed – refers to the flat surface of a printing press on which the block or plate is laid.

Bench hook – a tool that hooks onto a table with a stop to hold a block in place whilst it is being carved. Bench hooks can be found here.

Binder – (see medium) a clear substance to which pigment is added to create printmaking inks.

Bite – the action of an acid on a metal plate.

Blanket – used as cushions in printmaking presses between the roller and the paper.

Bleed – where ink appears outside the designed areas of a print. Digitally, bleed can also refer to the extension of the design beyond the cut or crop line to ensure the image runs to the edge of the print.

Blind emboss – an embossed impression in the paper, often made from a block without ink.

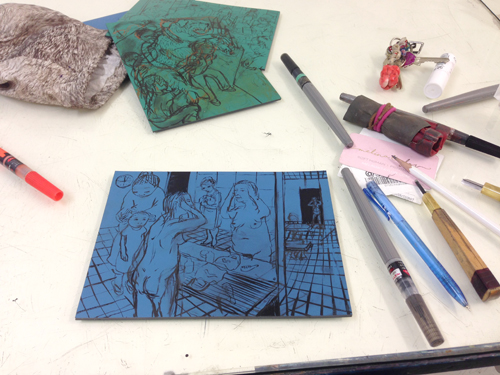

Block – the material into which a design is carved for relief printmaking, e.g. lino, ply etc.

Bon a tirer (BAT) – The first perfect print to come from the printing surface. This is usually made when the artist themselves is not printing the edition: a B.A.T print is used to show the print from which the whole edition should be matched. There is usually only one of these. See our blog post on editioning prints for more information.

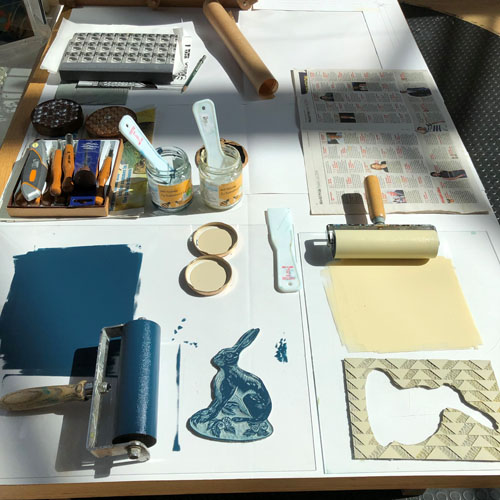

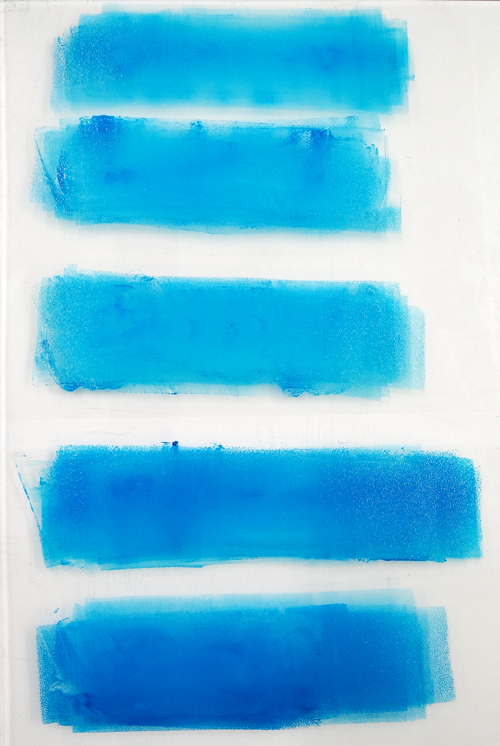

Brayer – a roller used to apply ink to a printing surface. Rollers can be found here.

Burin – an engraving tool with a metal shaft and usually a sharp V gouge point.

Burr – in drypoint, the ridge of metal (or plastic) thrown up on either side of the needle as it scratches into the plate. In mezzotint, the surface created by the action of the rocker.

Carborundum – silicon carbide – a fine powder used in intaglio printmaking. When applied to a plate, carborundum creates a rough, even surface that holds a lot of ink. Carborundum can also be used for levelling the surface of a lithography stone. Fine carborundum here.

Chine Collé – a process in which ink is transferred onto a thin sheet of paper (such as archival tissue paper) whilst simultaneously sticking the thin sheet to a stronger, thicker sheet of paper. Traditionally used to enable fine, delicate prints, now more often used to add areas of coloured paper to a single colour print. See more here.

Chop – a small mark printed in the margins of a print to show the maker. Traditionally, a chop shows the printer or publisher but is now sometimes used to show the artist.

CMYK – cyan, magenta, yellow and black. This colour system is used in halftone screen printing, where each colour is created as its own halftone exposed screen and printed separately, giving the overall look of a full-colour print.

Collagraph – a print made from a plate that has been layered with various natural and found materials to a base and then usually varnished. These are often printed using the intaglio method but can also be printed in relief. See our collagraph blog post here.

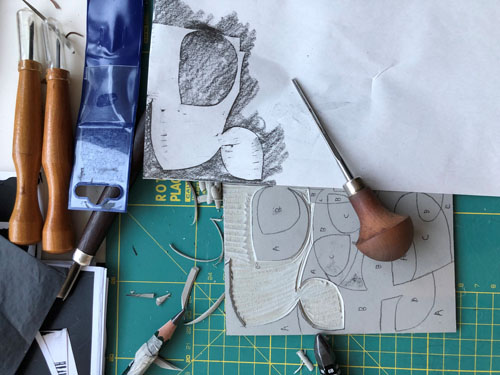

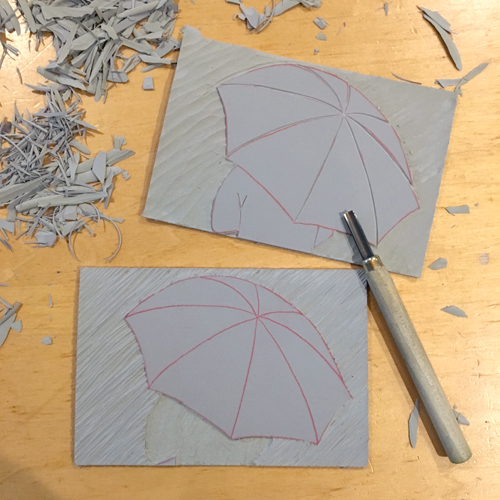

Cutting tool – a tool used for carving into a block. These can be V gouges, U gouges, hangito knives etc. Cutting tools can be found here.

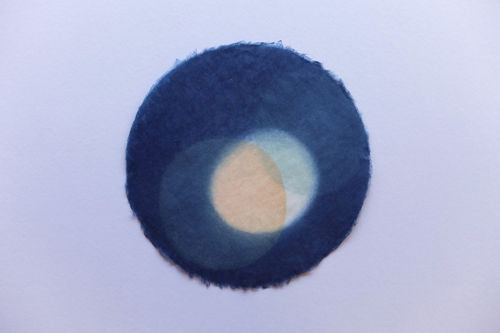

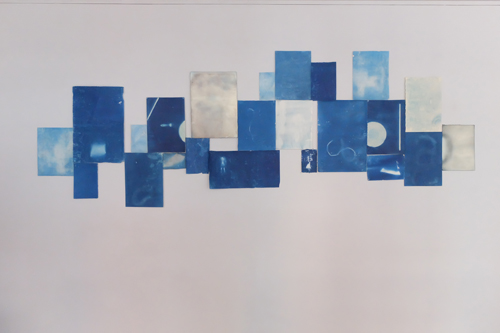

Cyanotype – an early form of photography that uses two solutions mixed together to create ‘blueprints’. Read more about making cyanotypes here.

Dabber/dauber – a wad of cloth used to apply ink to a block or plate. Also used to apply grounds to etching plates.

Deckled edge – A rough, irregular edge on a piece of printmaking paper.

DPI – dots per inch – the number of pixels in one inch of an image. 300dpi is usually standard for high-quality printing.

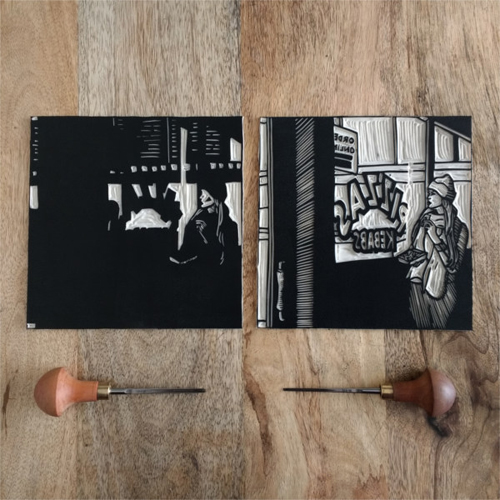

Drypoint – an intaglio printmaking method where an image is scratched onto a plate creating a burr that holds ink. See how to make a drypoint print here.

Durometer – measures hardness, for example, the shore of squeegees. The higher the number, the harder the material.

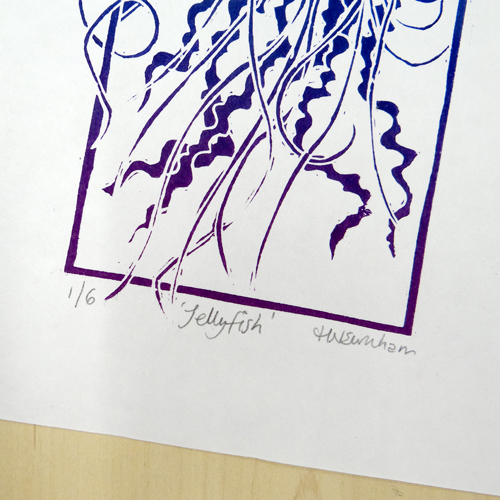

Edition – a set of identical prints taken from the same matrix or matrices (printing surfaces). Editions can either be limited or open. Limited editions mean that no more of the same prints will be made. Read more about editioning in our blog post here.

Emboss – an impression in the paper, often made from a block without ink.

Emulsion – when mixed with sensitiser, a photo emulsion can be used to coat screens to create exposed images for screen printing. Find emulsion here.

Engraving – a printmaking technique in which lines are carved directly into a plate using a burin.

Etching – an intaglio technique in which a plate is prepared with resistant material before being exposed to an acid that bites into the remaining surface. When charged with ink, the bitten surface retains the ink, allowing the design to be printed. The term ‘etching’ is also used to refer to similar techniques such as ‘drypoint etching’ where no acid is used.

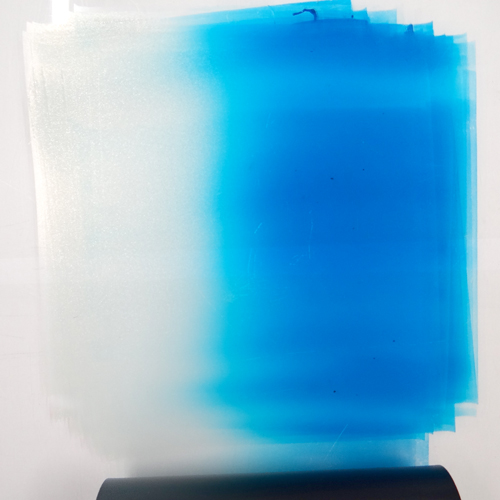

Exposure – in screen printing, where a screen coated with sensitised emulsion is exposed to a light source with a design on a transparency between the screen and the light. The light hardens the emulsion it can reach, leaving the areas of the design soft and washable. This results in a screen with areas of open mesh in the desired design.

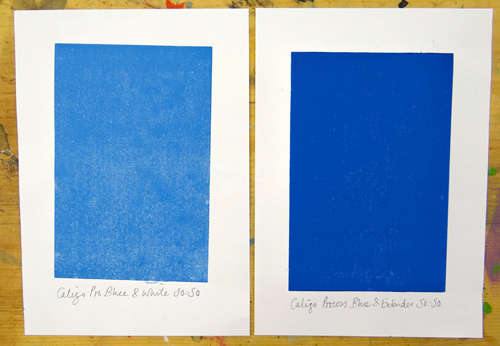

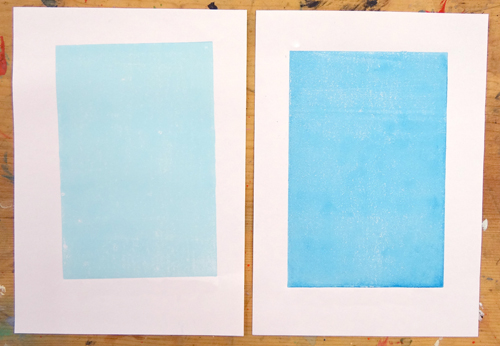

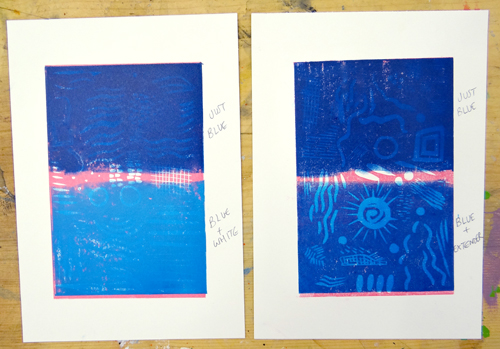

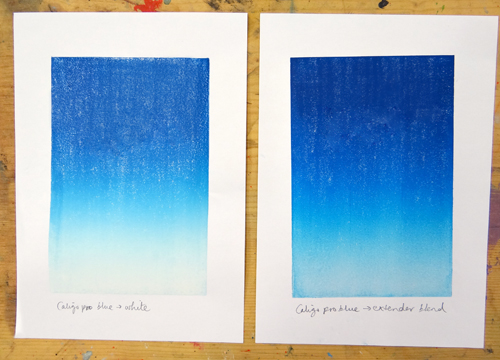

Extender – a transparent modifier to add to ink. Adding extender can make the colour more transparent and can loosen the ink.

Giclée – an archival fine art digital printmaking process.

Gouge -A tool used to carve a block for relief printing. Can have a V or a U shaped end.

Halftone – The breakdown of an image into small dots to simulate the look of continuous tones. Greyscale images need to be broken down into halftones in order to be exposed onto screens for screen printing. More about halftones here.

Hand burnish – taking a print by hand or by using a baren instead of a press. Paper is placed over the inked up block and then rubbed over with a hand, baren, wooden spoon or similar to transfer the ink to the paper.

Hangito – a Japanese Woodblock Printing cutting tool that looks like an angled sharp knife with one bevelled edge. Find hangitos here.

Hardground – a substance added to the surface of an etching plate to resist acid. A hardground can be drawn into with a sharp tool to reveal areas of metal to the acid bath.

Honing – sharpening or maintaining a sharp edge on a cutting tool.

Intaglio – a printmaking method using an image that has been incised into a plate. Ink is worked into the recesses of the plate and is usually printed onto dampened paper through an etching press. Drypoints, etchings and collagraphs can all be printed intaglio.

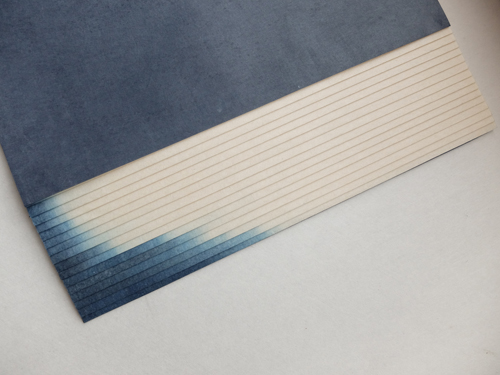

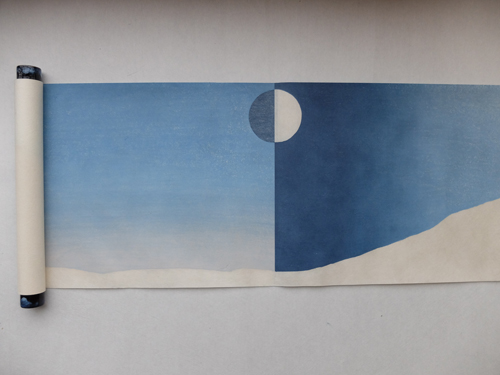

Japanese Woodblock (Mokuhanga) – a type of relief printmaking in which brushes are used to ink up a woodblock with watercolour paint and nori paste. Images are printed onto dampened paper in layers, often registered using kento marks. Learn more about Japanese Woodblock here.

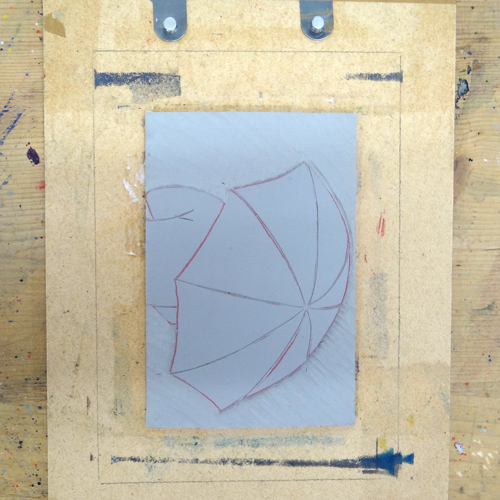

Key block – the key layer in a print that gives the main detail or outline of an image. Usually printed first or last in a multi-layered print.

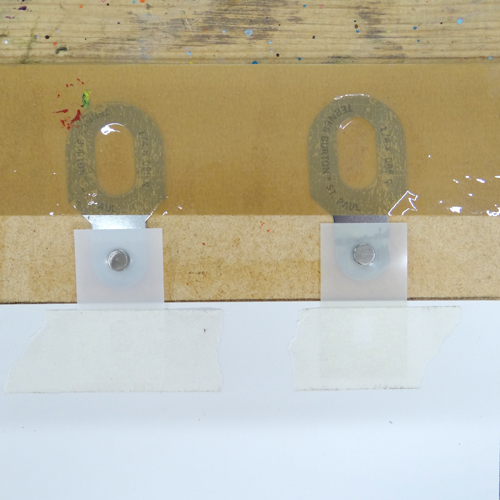

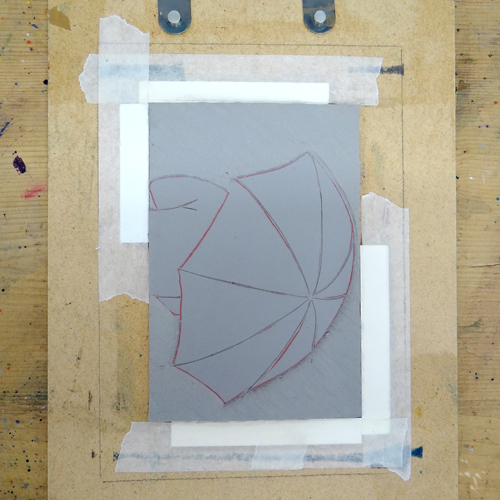

Kento – Japanese Woodblock method of registration. Kento marks are cut into a block using a kento chisel. The corner of the paper slots into these marks so that the paper rests in the same place for each layer. Shop for kento chisels, kento stickers and kento boards.

Kitchen Lithography – a form of printmaking that uses the same principles as lithography but uses simple household materials such as aluminium foil and cola!

Letterpress – the practice of printing by hand setting (composition) of lead and wood type and printing using a number of different presses. Letterpress printing remained the primary way to print until the second half of the 20th century.

Lightfastness – usually refers to paper and inks. Change caused by exposure to light.

Limited edition – a set of identical prints taken from the same matrix or matrices (printing surfaces). Limited editions mean that no more of the same prints will be made. Read more about editioning here.

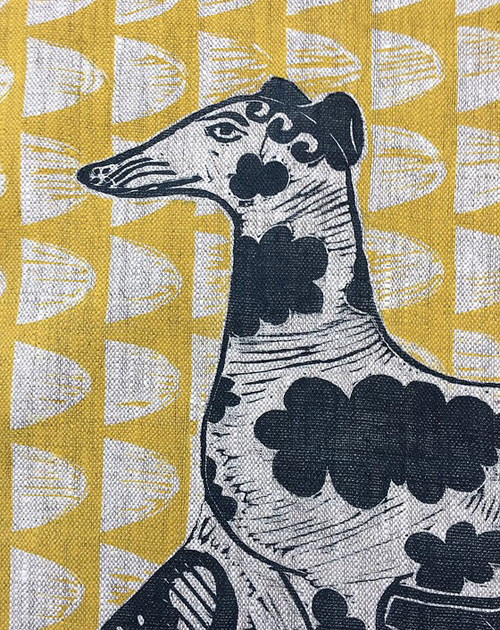

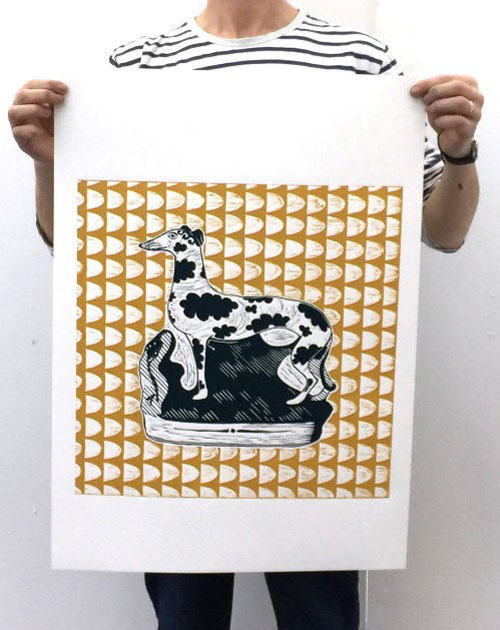

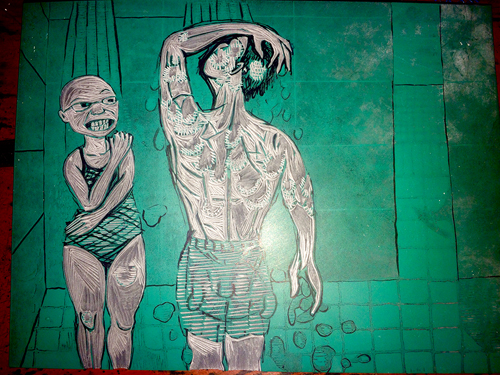

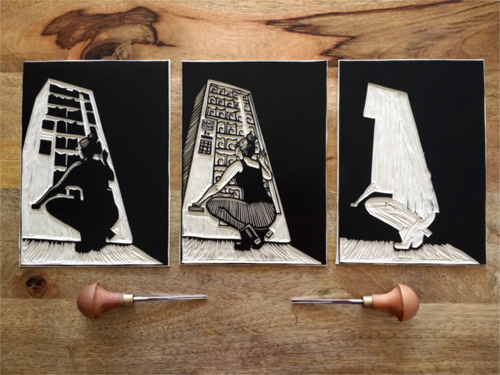

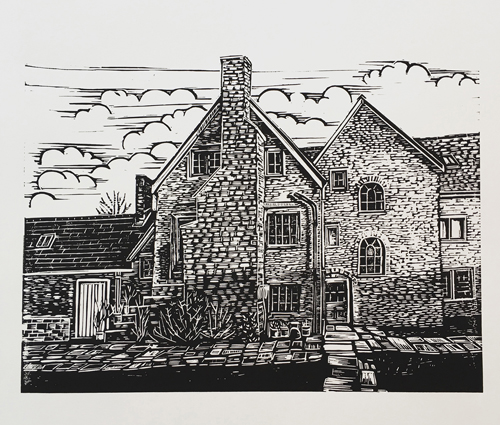

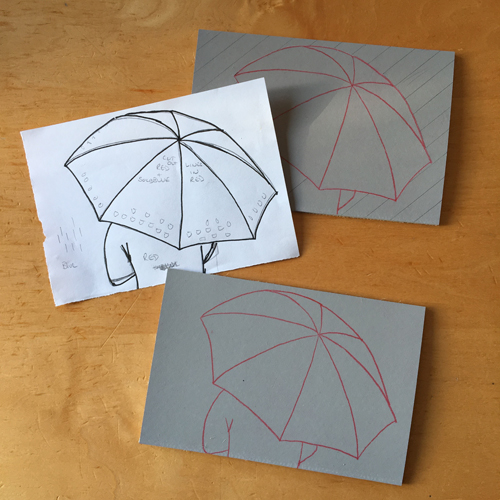

Lino – linoleum – a material made of cork dust and linseed oil with a hessian backing. Used to create relief prints when carved. Shop for lino here.

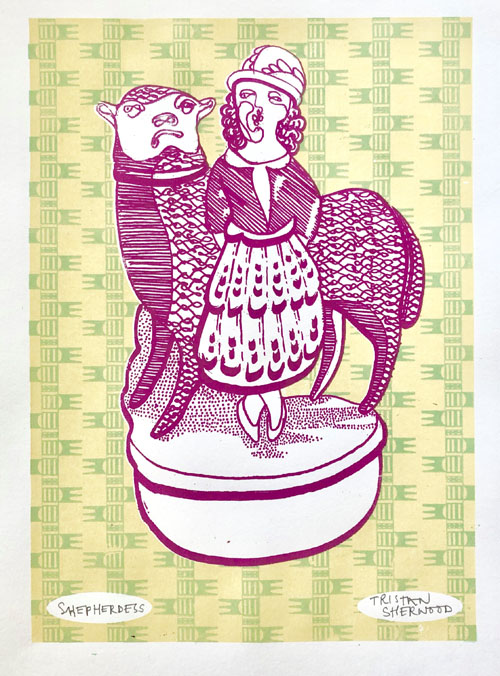

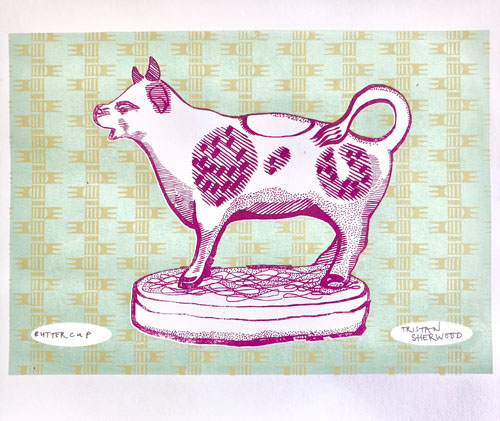

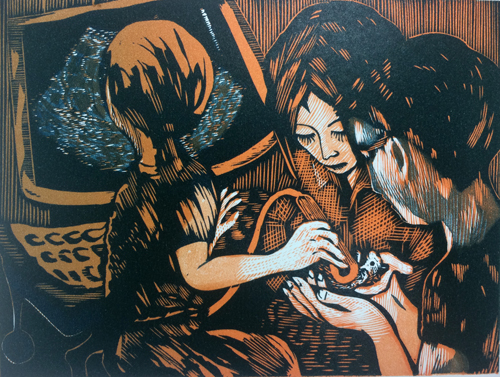

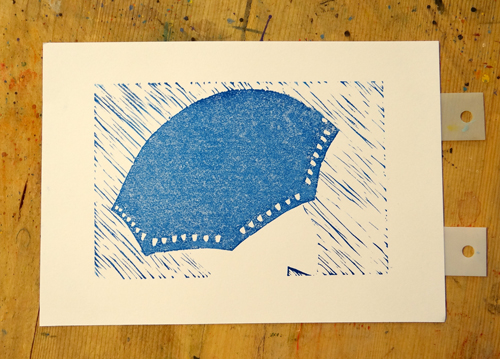

Linocut – a relief print made using a carved piece of lino. Learn to make a linocut on our blog post.

Lithography – a planographic printmaking process in which ink is applied to a grease-treated image on a flat surface. Moisture repels oil-based ink from the blank areas and the greasy areas attract ink.

Matrix – the printmaking surface – plate, block, stone etc. from which the image is taken.

Medium (printing medium) – a clear substance to which paint is added to create printmaking inks.

Mesh – the woven fabric stretched over a frame to make a silkscreen for screen printing.

Mezzotint – a printmaking technique in which a plate is textured with a rocker to create dark tone. The tonal areas are then polished back to a smooth surface that will not hold ink. The plate is printed intaglio.

Mokuhanga (Japanese Woodblock) – a type of relief printmaking in which brushes are used to ink up a woodblock with watercolour paint and nori paste. Images are printed onto dampened paper in layers, often registered using kento marks. (Moku = wood and Hanga = printmaking).

Learn more about Japanese Woodblock here.

Mokulito – a form of Japanese printmaking meaning ‘wood lithography’. An image is drawn onto the block using greasy materials.

Monoprint – a print made using any printmaking technique from which only one print can be made. Monoprints can be made using and single or multiple printmaking techniques and usually is made using some form of matrix.

Monotype – like a monoprint, a monotype is a print that is one of a kind. Unlike monoprints, monotypes are not made using a matrix such as a cut block or plate.

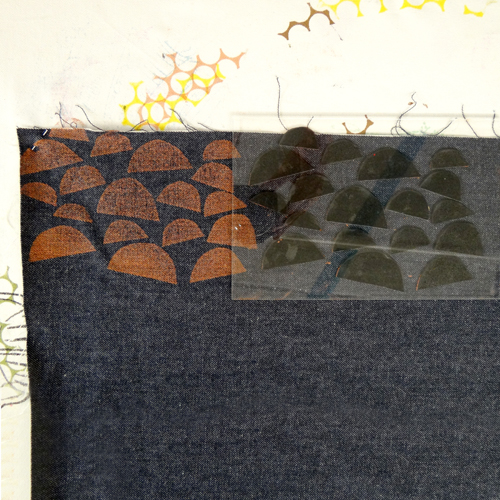

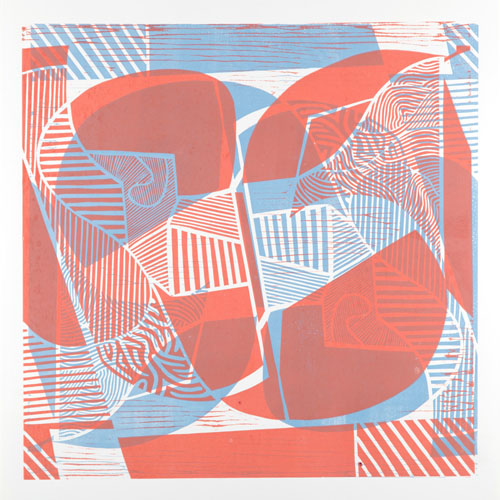

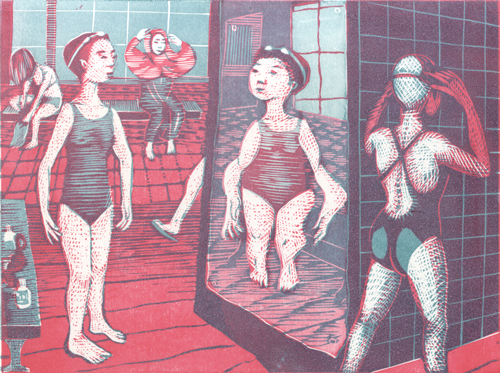

Multi-Block – a relief print that is made using multiple blocks that print on top of one another to create a multi-coloured final print.

Noise – the marks left behind on a print from areas of a block that have been carved away and have picked up ink from the roller. Sometimes these marks are left to add character or movement to a print.

Nori – starch paste used in Japanese Woodblock Printing. Can also be used for chine collé printing. Shop for nori.

Offset – transferring ink from one surface to another.

Oil-based – inks that use oil as their vehicle (usually linseed oil). Traditionally these need to be cleaned up with solvents but alternatives can now be used: Zest-it can be used for clean up of oil-based inks. Cranfield also make an oil-based but water-washable ink called Caligo which can be washed up with soap and water.

Opaque – impenetrable by light, opposite of transparent, not see-through. Refers to inks that do not show any colour of the paper, fabric or previous print layers through.

Original print – original prints are prints in the medium the artist originally used e.g. linocuts, collagraphs, lithographs, etchings, screenprints etc. This is not the same as a reproduction which is usually digitally printed.

Overprinting – colours are printed over the top of one another.

Paper fingers – folded pieces of paper or card used to protect paper and blankets from finger marks.

Photo Emulsion – when mixed with sensitiser, a photo emulsion can be used to coat screens to create exposed images for screen printing. Find emulsion here.

Pigment – the coloured particles in an ink.

Planography – a printing process, such as lithography, that prints from a flat surface. The printing and non-printing areas exist n the same plane and rely on chemical properties to hold or repel ink.

Plate – a metal, card or plastic surface used to create an image, usually used when printing intaglio.

Platemark – The embossed mark left on a print made by the edges of the plate when printing through an etching press.

Plate tone – in intaglio printing, the faint tone printed from a plate by the residue of ink left on the plate after wiping.

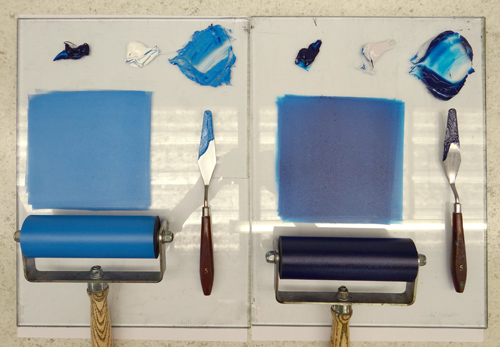

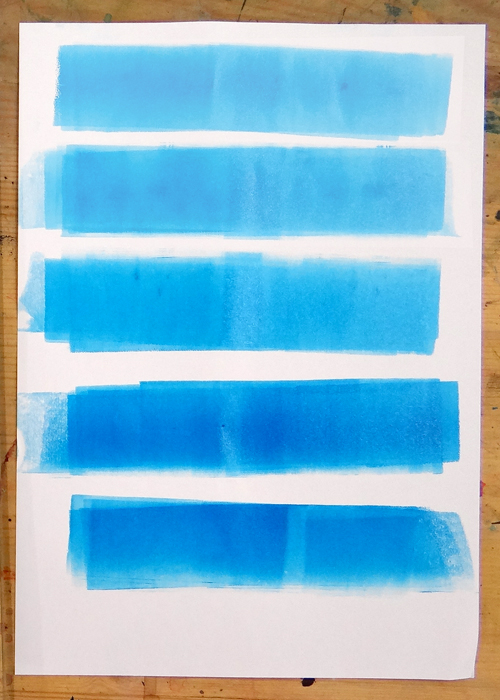

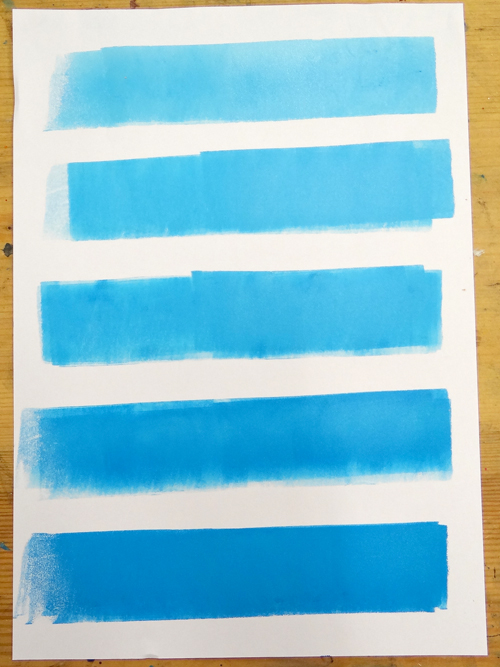

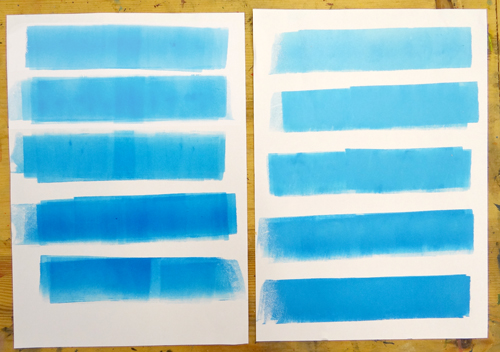

Process colours – printmaker’s primary colours. Process cyan, magenta and yellow inks can be mixed together to create a wide spectrum of colours. Process colours are often more transparent than other inks and allow for overprinting to create more colours that mix on the surface of a print.

Proof – Artist’s proof prints are made by the artist to check the print quality and design before printing an edition. Artist’s Proof prints usually shouldn’t exceed 10% of the overall number in the edition. They are usually identical to the edition but may sometimes include slightly flawed prints omitted from the edition. See our blog post on editioning prints for more information.

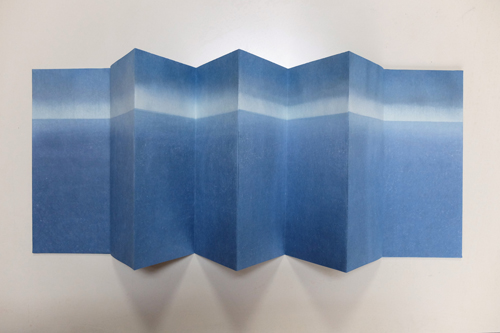

Rainbow roll – When more than one adjacent colour is rolled out onto a plate and mixed in a gradient as the ink is rolled out. See the use of a rainbow roll here.

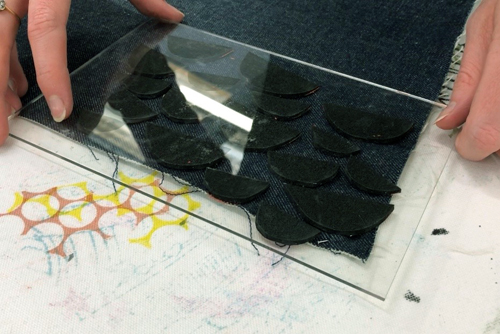

Reduction – a relief printing method in which the same block is carved into between each layer, leaving a smaller printing surface with each layer. See a reduction linocut here.

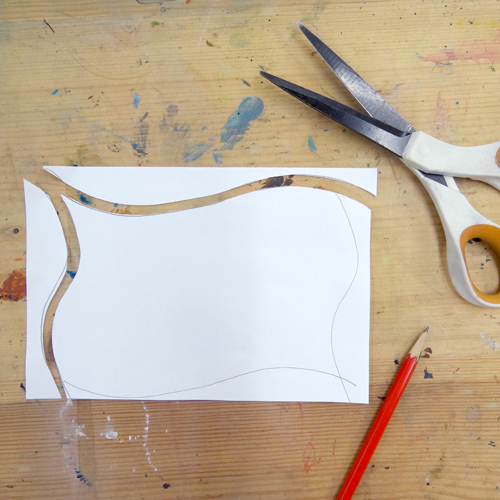

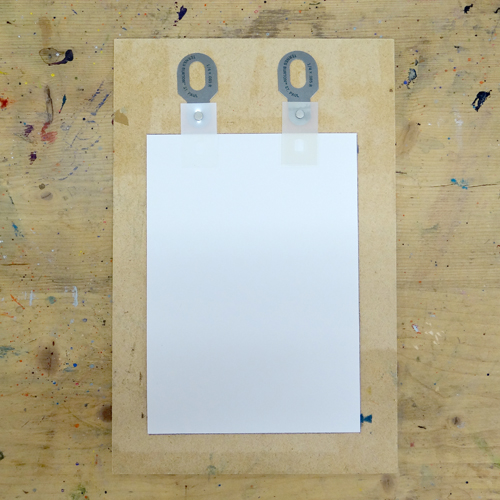

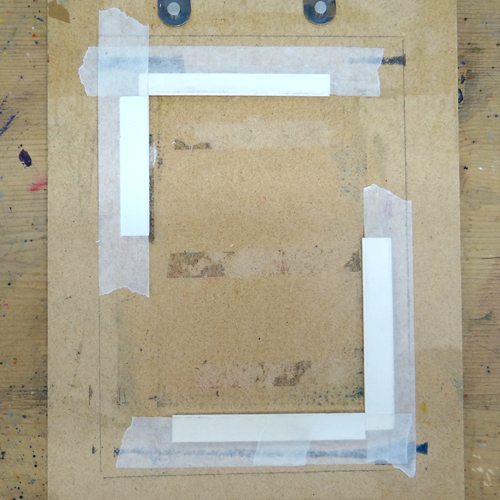

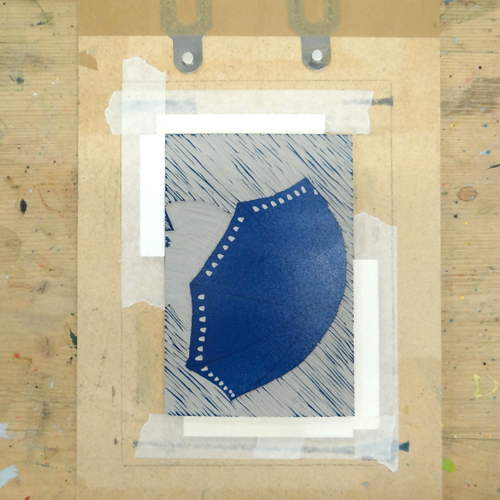

Registration – the lining up of print layers or a single print layer onto the substrate.

Registration marks – guides drawn or carved to aid in the proper positioning of matrix and substrate in the printing process.

Relief printing – a printmaking process where the unwanted areas of a block are carved away. The raised areas of the block are charged with ink (usually using a roller) and printed onto a substrate such as paper or fabric. E.g. linocut and woodcut.

Retarder – An ink modifier used to slow down the drying time of ink.

Screen (silkscreen) – Mesh is stretched over a frame to be used for screen printing. A stencil is created on the mesh with paper or by using Photo Emulsion.

Screen film – a transparency on which a design can be digitally printed or hand-drawn, used to expose an image onto a screen for screen printing.

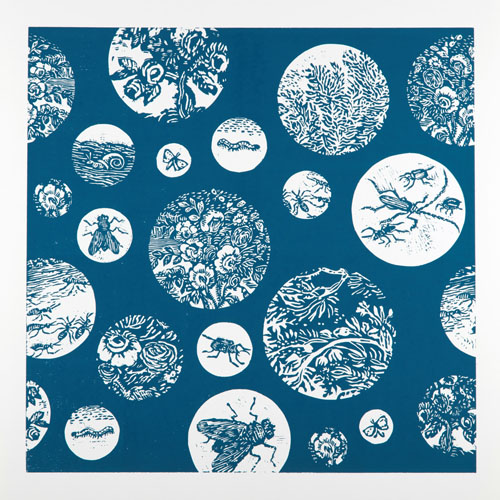

Screenprint – a print made using a screen printing technique.

Screen printing – a printmaking technique that uses a squeegee to force ink through a mesh-stretched screen onto a substrate. Stencils made of paper or exposed onto the mesh using photo emulsion are used to create a design.

Scrim (tarlatan) – rough, loosely woven fabric used in intaglio printing to wipe ink from the plate. Buy scrim here.

Serigraphy – screen printing, referring to a fine art process rather than the commercial process.

Shellac – varnish made from lack resin dissolved in methylated spirits. used to seal collagraph plates.

Shore – hardness, durometer. Used when referring to screen printing squeegees.

Silkscreen – Mesh is stretched over a frame to be used for screen printing. A stencil is created on the mesh with paper or by using Photo Emulsion. Find screens here.

Sizing – a water-resistant coating added to paper.

Snap-off – the distance between a screen and the paper.

Softground – a substance added to the surface of an etching plate to resist acid. A softground can be pressed into with soft tools and objects to create subtle marks and textures before placing in the acid bath.

Solvent – a substance used to dissolve others, often used to clean up oil-based inks.

Spit-bite – an etching technique in which acid is applied to the plate with a brush and water or saliva.

Squeegee – a screen printing tool with a rubber blade fixed to a metal or wooden handle. The blade is used to force ink along the screen and through the mesh. Shop for squeegees.

Stop Out – an acid-resistant substance used in etching to protect an area of metal plate from an acid bath.

Sugarlift – an etching technique in which a sugary solution is painted onto a metal plate. The plate is covered with ground and then washed. The sugar dissolves, exposing areas of the metal which can then be etched in an acid bath.

Sumi – Chinese black ink. Find it here.

Tarlatan (scrim) – rough, loosely woven fabric used in intaglio printing to wipe ink from the plate. Buy scrim here.

Thermofax – a screen made using a carbon photocopy and a thermofax machine, printed with a squeegee in a similar way to screen printing. Get your own thermofaxes here.

Transparent Base – an ink modifier used particularly in screen printing to make ink more transparent.

Trap – the areas of overlap between layers in a print.

Tusche – a greasy drawing medium in the form of a stick or a liquid, used mainly in lithography.

Tympan – a greased plate on a lithographic press

Vinyl – a block that can be carved and printed in a similar way to lino.

Viscosity – the fluidity of an ink.

Viscosity printing – a method of using multiple colours from one plate by using inks of different viscosities.

Water-based – inks that use water as a vehicle. These can be cleaned up with water and tend to dry more quickly than oil-based inks.

Wet-on-dry – printing one colour over the top of another when the first layer has dried.

Wet-on-wet – printing one colour over the top of another whilst the first is still wet.

Whetstone – an abrasive stone used for sharpening tools.

Wiping – in intaglio printmaking where ink is removed from the surface of the plate.

Woodcut – a relief printing process where an image is cut from the plank side of the wood.

Wood Engraving – a printmaking technique in which lines are carved directly into the end grain of a piece of wood.

This glossary is gathered from a few sources including ‘Printmaking: Traditional and Contemporary Techniques’ by Ann D’Arcy Hughes and Hebe Vernon-Morris as well as https://www.annieday.com.au/glossary-printmaking–papermaking-terms